Outcrossing Debates: The Battle for Genetic Diversity#

This is a controversial topic. If you mention “Outcrossing” in a room of breeders, half will cheer, and the other half will leave the room.

But as an owner, you need to understand it because it affects your cat’s health.

The Maine Coon breed has a secret problem: Inbreeding. Not necessarily brother-to-sister inbreeding, but deep, historical inbreeding that dates back to the 1970s.

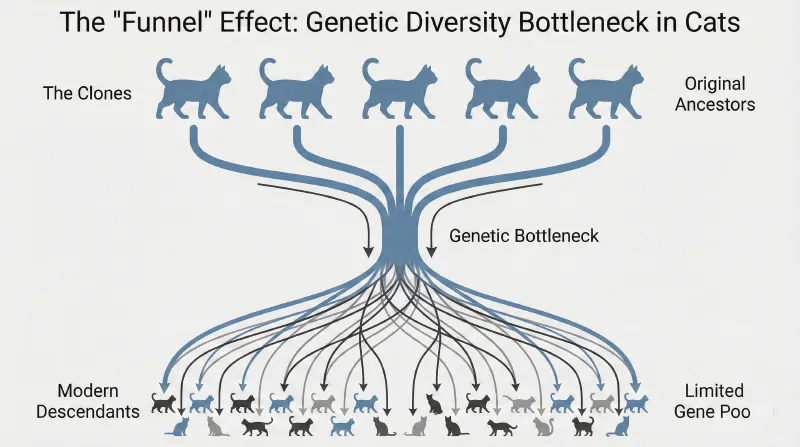

We touched on this in our Pedigree Guide, but today we are going deeper. We are talking about The Clones, the Genetic Bottleneck, and the brave breeders trying to fix it.

The 35% Problem (The Clones)#

In 1978, a single pair of cats produced offspring that looked perfect. They had the boxy muzzle, the ear tufts, and the heavy boning that judges loved.

Breeders went crazy for them. Everyone wanted those genes. They bred those cats, and their children, and their grandchildren, into almost every line in existence.

Today, if you analyze the DNA of the average Maine Coon, approximately 35% to 40% of their genes come from just five specific cats (The Clones).

This reduces the immune system’s ability to fight disease. It concentrates bad genes (like HCM and SMA).

What is Outcrossing?#

Outcrossing is the practice of introducing “new blood” into the breed.

Since the Maine Coon “stud book” is still theoretically open in some registries (like ACA), breeders can find domestic cats in Maine that physically match the breed standard (the “Phenotype”) but have no papered ancestors.

These cats are called Foundation Cats.

The Process:

- Selection: A breeder finds a large, long-haired farm cat in Maine.

- Certification: Judges examine the cat. If it looks like a Maine Coon, it is registered as “Generation 0” (F0).

- Breeding Up: This cat is bred to a pedigreed Maine Coon. The kittens are F1.

- Acceptance: By the 3rd or 4th generation, the kittens are considered full Maine Coons, but they carry fresh, unrelated genes.

The Controversy#

Why is this controversial?

- Unpredictability: “Foundation” cats might carry unknown diseases or traits (like bad temperaments) that pedigreed lines have bred out.

- The “Type”: F1 and F2 kittens often don’t look like “Show” Maine Coons. Their ears might be smaller; their muzzle less square. Breeders have to sacrifice the “perfect look” for a generation or two to get the health benefits.

Why You Should Care (The “Low Clone” Kitten)#

When you are buying a kitten, asking about “Clones” or “Foundation” tells the breeder you are educated.

A “Low Clone” cat is generally considered one with less than 20% Clone genetics. These cats often have:

- Stronger immune systems (less gingivitis/viruses).

- Larger litter sizes (higher fertility).

- Potentially longer lifespans.

They might not always win “Best in Show” because they don’t have the extreme, exaggerated features of highly inbred lines, but they are often healthier pets.

Conclusion#

The battle for diversity is a battle for the survival of the breed. We don’t want the Maine Coon to go the way of the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel (riddled with genetic heart issues). Supporting breeders who outcross is supporting the future of the giant cat we love.

Resources & Further Reading#

- PawPeds. (2024). The Clone Percentage Explained.

- Maine Coon Heritage Site. (n.d.). Foundation Lines and Diversity.