Hip Dysplasia: The ‘Maine Coon Walk’ Myth#

There is a pervasive myth in the Maine Coon community that often prevents owners from seeking necessary veterinary care. It is the idea of the “Maine Coon Swagger.” Owners will observe their large cat walking with a pronounced wiggle, their hindquarters swaying side to side with every step, and assume it is simply a quirk of the breed’s massive size. In reality, this swagger is rarely a benign breed trait; it is a biomechanical compensation for pain. It is the classic clinical sign of Hip Dysplasia, a degenerative joint disease that affects nearly a quarter of the breed.

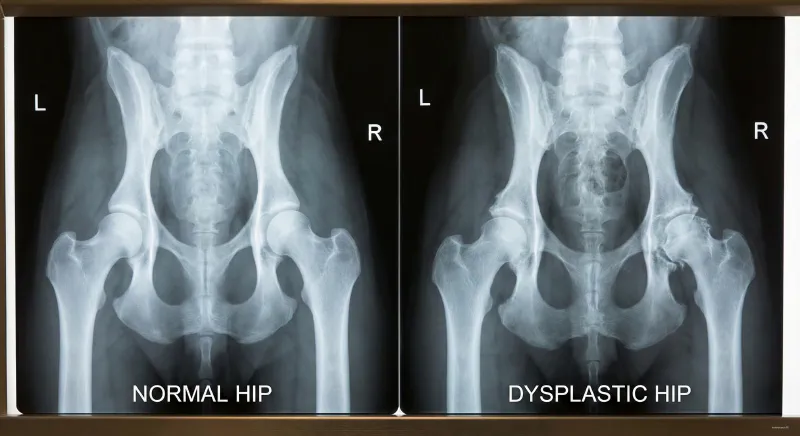

According to data from the Orthopedic Foundation for Animals (OFA), Maine Coons have one of the highest incidences of hip dysplasia among all cat breeds. This condition occurs when the hip joint—a ball-and-socket mechanism—develops abnormally. In a healthy hip, the femoral head (the ball) sits deeply and tightly within the acetabulum (the socket), rotating smoothly with every step. In a dysplastic hip, the socket is too shallow or the ball is misshapen. Instead of gliding, the bones grind against each other. This looseness, or laxity, causes chronic inflammation, eventually leading to the body laying down calcium deposits (arthritis) in a desperate attempt to stabilize the wobbly joint.

Understanding the mechanics of this disease is critical because cats are stoic. A dog with hip dysplasia will often yelp or limp visibly. A Maine Coon will simply change its lifestyle. They are masters of masking discomfort, which means the “symptoms” are often behavioral rather than vocal.

The most reliable indicator of hip pain in a Maine Coon is the “Bunny Hop.” When a healthy cat runs, its legs move independently, extending fully. A cat with hip dysplasia will often move both rear legs forward simultaneously, hopping like a rabbit. This gait minimizes the extension and rotation of the hip joint, reducing the grinding sensation. Other subtle signs include a reluctance to jump. If your cat hesitates before leaping onto the sofa, “pumps” their legs several times before taking off, or pulls themselves up by their front claws instead of propelling from the back, their hips are likely the culprit. You may also notice they sit “sloppy,” with one or both legs kicked out to the side rather than tucked neatly under the body, as the tight tuck places pressure on the inflamed joint capsule.

The genetics of Hip Dysplasia are frustratingly complex. Unlike PK Deficiency or SMA, which are controlled by single gene mutations, Hip Dysplasia is a polygenic trait. This means it is controlled by a combination of many different genes working together. Because of this, two parents with “Good” hips on their X-rays can still produce a kitten with dysplastic hips if the recessive gene combinations align poorly. This is why Ethical Breeders rely on the OFA grading system. By X-raying breeding cats at two years of age and removing those with “Fair” or “Dysplastic” hips from the program, they can statistically reduce the prevalence of the disease, even if they cannot eliminate it entirely.

While you cannot change your cat’s genetics, you have absolute control over the environmental factors that worsen the disease. The single most important factor is weight. Physics dictates that every extra pound of body mass places exponential force on the joints. A Maine Coon that is overweight is not just “fluffy”; they are in accelerated decline. Keeping your cat at a lean Body Condition Score is the most effective painkiller available. If you cannot feel your cat’s ribs easily, they are carrying too much weight for their hips to handle.

Management of a dysplastic cat requires a proactive approach. You should not wait for the cat to limp before offering support. I recommend starting all Maine Coons on a high-quality joint supplement containing Glucosamine, Chondroitin, and MSM by the age of two. Products like Dasuquin or Cosequin provide the building blocks for cartilage repair and can slow the degradation of the joint. For cats already showing signs of pain, the environment must be modified. Slippery hardwood floors are treacherous for dysplastic cats; the lack of traction causes their legs to slide outward, torquing the hip capsule. Placing yoga mats or carpet runners in high-traffic areas and using Pet Steps for high furniture can drastically improve their quality of life.

Nutramax Dasuquin for Cats

The premier joint supplement for dysplastic cats. Contains ASU (avocado/soybean unsaponifiables) which protects cartilage better than Glucosamine alone.

Check Price on Amazon →Ultimately, a diagnosis of Hip Dysplasia is not a death sentence. It is a management challenge. With weight control, environmental modifications, and modern pain management (such as the new monoclonal antibody treatments for Arthritis), even a cat with “bad hips” can live a comfortable, active life. The key is to stop viewing the sway as “cute” and start viewing it as a medical condition that needs support.

References#

- Loder, R.T. & Todhunter, R.J. (2017). The Demographics of Hip Dysplasia in the Maine Coon Cat. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery.

- Perry, K. (2016). Feline Hip Dysplasia: A Challenge to Recognise and Treat. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery.

- Orthopedic Foundation for Animals (OFA). Hip Dysplasia Statistics and Breed Comparisons.