Maine Coon Dental Health: Stomatitis, Gingivitis & The Red Line#

When discussing the health liabilities of the Maine Coon, the conversation is almost exclusively dominated by the size of their heart and the stability of their hips. While Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy and Hip Dysplasia are critical concerns, there is a third, equally pervasive genetic weakness that plagues the breed: their oral hygiene. Experienced breeders often warn that Maine Coons have “bad mouths,” a colloquialism that understates a painful reality. This breed is genetically predisposed to aggressive, immune-mediated gum diseases that can manifest as early as six months of age. For the Maine Coon owner, checking the mouth is not an optional grooming task; it is a mandatory medical surveillance routine.

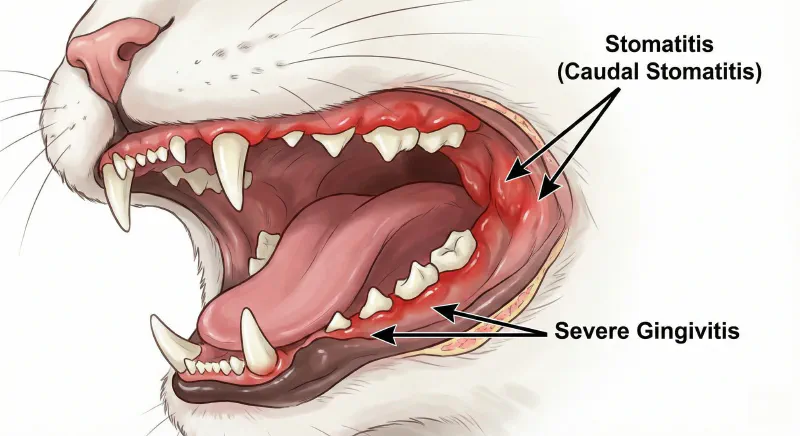

The most common early warning sign in this breed is a condition known as Feline Juvenile Gingivitis. It typically appears during the teething phase, between five and ten months of age, when the adult teeth are erupting. In a standard cat, the gums might become slightly swollen for a few weeks before settling into a healthy, pale pink. In many Maine Coons, however, the immune system overreacts to the eruption of the teeth and the introduction of new oral bacteria. The gums turn an angry, inflamed crimson, particularly along the gumline where the tissue meets the tooth. This “Red Line” is the hallmark of the condition. While some cats grow out of this phase by their second birthday with the help of aggressive dental hygiene, for others, it is the precursor to a lifelong battle with oral inflammation.

If Juvenile Gingivitis is left untreated, or if the cat has the genetic misfortune of a hyper-active immune system, the condition can progress into Feline Chronic Gingivostomatitis (FCGS), often simply called Stomatitis. This is not merely “bad gums”; it is a debilitating autoimmune disease where the cat’s body develops an allergy to the plaque on its own teeth. The inflammation spreads beyond the gums to the fauces—the back of the throat—turning the entire oral cavity into an ulcerated, bleeding wound. The pain associated with Stomatitis is excruciating, comparable to having a mouth full of severe canker sores. Owners often mistake the symptoms for pickiness; the cat approaches the food bowl, hungry and eager, only to hiss at the food or run away after one bite because the mechanical act of eating causes agony.

Treating Stomatitis in Maine Coons is complex because the root cause is the immune system, not just the teeth. While antibiotics and steroids can provide temporary relief by reducing the bacterial load and inflammation, they are rarely a cure. The steroids lose effectiveness over time, and long-term use carries its own risks, such as diabetes. For many cats, the only permanent solution is a Full Mouth Extraction. This procedure sounds barbaric to the uninitiated owner, but it is curative. By removing the teeth—the surface on which the plaque adheres—the immune system no longer has a trigger to attack. Post-surgery, these toothless giants recover remarkably well, often returning to eating dry kibble (which they swallow whole) with more enthusiasm than they did when they had a mouthful of painful teeth.

Prevention, or at least management, relies on reducing the bacterial load in the mouth before the immune system can react to it. This requires a commitment to daily brushing. The idea of brushing a cat’s teeth is often treated as a joke, but for a Maine Coon, it is a medical necessity. The key is to use an enzymatic toothpaste formulated for felines. Unlike human toothpaste, which relies on scrubbing abrasives, feline toothpaste uses enzymes to chemically break down the plaque biofilm. This means you do not need to scrub vigorously; you simply need to get the paste onto the teeth and gums.

Virbac C.E.T. Enzymatic Toothpaste (Poultry Flavor)

The gold standard for feline dental care. This enzymatic formula breaks down plaque chemically, meaning you don't have to scrub perfectly to get results.

Check Price on Amazon →Training a Maine Coon to accept brushing leverages their high intelligence and food motivation. The process must be gradual, starting with letting the cat lick the poultry or malt-flavored paste off a finger. Once they associate the flavor with a treat, you can introduce a finger brush or a small, soft-bristled toothbrush. The goal is to gently lift the lip and swipe the paste along the upper molars and canines, where tartar accumulation is heaviest. Consistency is more important than duration; ten seconds of brushing every day is infinitely more effective than a ten-minute wrestling match once a month.

It is also critical to understand the intersection of dental health and other breed-specific risks. Dental procedures require general anesthesia, which carries a higher risk profile for Maine Coons due to the prevalence of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Before any dental surgery, including routine cleanings, a responsible owner should insist on a pre-anesthetic blood panel and, ideally, a recent pro-BNP test or echocardiogram to ensure the heart can handle the sedation. Neglecting dental health inevitably leads to a situation where an older cat with heart disease needs urgent dental surgery, creating a dangerous medical dilemma that could have been avoided with preventative care.

Ultimately, the state of your Maine Coon’s mouth is a window into their overall immune health. That thin red line on the gums is a distress signal. By inspecting their mouth weekly, committing to enzymatic hygiene, and recognizing the signs of oral pain, you can prevent your gentle giant from suffering in silence.

References#

- Winer, J.N., Arzi, B., & Verstraete, F.J. (2016). Therapeutic Management of Feline Chronic Gingivostomatitis: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Frontiers in Veterinary Science.

- Reiter, A.M. (2018). Pathophysiology of Dental Disease in the Cat. Veterinary Clinics: Small Animal Practice.

- Pedersen, N.C. (1991). Feline Husbandry: Diseases and Management in the Multiple-Cat Environment. American Veterinary Publications.