Parasite Control for Giants: The ‘Invisible’ Worms#

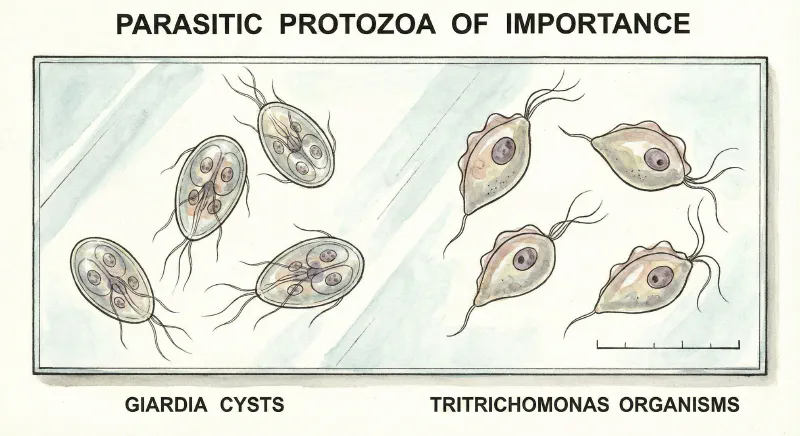

When most cat owners think of parasites, they picture a flea jumping on the sofa or a visible roundworm in the litter box. For the Maine Coon owner, however, the most dangerous threats are often the ones you cannot see without a microscope. Because Maine Coons are frequently raised in community environments—catteries where kittens are socialized in groups—they are statistically more prone to a specific class of “invisible” parasites known as protozoa. These microscopic organisms, specifically Giardia and Tritrichomonas Foetus, are the primary drivers behind the breed’s notorious reputation for Soft Stool and Diarrhea.

Understanding the difference between a standard worm (helminth) and a protozoan infection is critical for treatment. A standard deworming pill bought at a pet store might kill roundworms, but it will do absolutely nothing against the single-celled organisms that are actively destroying your cat’s intestinal lining. If your Maine Coon has a ravenous appetite but suffers from chronic, foul-smelling loose stool, you are likely not dealing with a food allergy; you are dealing with a cattery parasite.

The most persistent enemy in the Maine Coon world is Tritrichomonas Foetus (TF). Often called the “Cattery Curse,” this protozoan causes chronic large-bowel diarrhea. The classic symptom is “cow pie” stool that is incredibly malodorous, often finishing with a drop of fresh blood or mucus. The cat typically appears healthy, active, and has a normal coat, which makes the diagnosis confusing for owners who assume a sick cat should act sick. Standard fecal flotation tests performed at many vet clinics often miss TF because the organism is fragile and dies quickly outside the body. To diagnose it, you must request a specific PCR (DNA) diarrhea panel. Treatment is difficult and often requires a neurological antibiotic called Ronidazole, which must be carefully dosed by a veterinarian to avoid toxicity.

Giardia is the other “invisible” twin. Unlike TF, Giardia is a zoonotic risk, meaning it can be transmitted to humans. It creates a greasy, pale stool and can lead to significant weight loss as the parasites block nutrient absorption in the gut. The challenge with Giardia in long-haired breeds like the Maine Coon is reinfection. The cysts are sticky and cling to the fur on the “pantaloons” and tail. Even if you treat the cat with medication (typically Fenbendazole/Panacur), the cat will groom itself, ingest the cysts stuck to its fur, and reinfect its gut. Therefore, successful treatment of Giardia requires a “medicate and bathe” protocol: treating the cat internally while simultaneously bathing the hindquarters to remove cysts from the coat.

While protozoa wreak havoc internally, external parasites like fleas and ticks pose a specific threat to the Maine Coon’s massive coat. A single flea bite can trigger Feline Miliary Dermatitis, an allergic reaction that causes crusty lesions along the spine and neck. In a dense, triple-coated cat, you may never see the flea itself. You will only feel the scabs when you are petting them.

The debate between collars and topical treatments is settled by the fur texture. Flea collars rely on contact with the skin to release chemicals. The Maine Coon’s thick ruff often lifts the collar away from the skin, rendering it less effective and potentially causing matting around the neck. Topical spot-on treatments are generally superior for this breed. Products like Revolution Plus are widely favored by breeders because they are “broad spectrum”—they kill fleas, ticks, ear mites, and, crucially, heartworms.

Heartworm disease in cats is fundamentally different from dogs and is often misdiagnosed as Feline Asthma. In cats, the condition is known as HARD (Heartworm Associated Respiratory Disease). The worms do not just clog the heart; they cause a severe inflammatory reaction in the lungs. Sudden coughing, wheezing, or even sudden death can be the first and only sign of infection. Since there is no safe treatment to kill adult heartworms in cats (the arsenic-based drugs used for dogs are toxic to felines), prevention is the only option. If you live in an area with mosquitoes, a monthly preventative is mandatory, even for indoor cats.

Finally, there is the visible menace: the Tapeworm. If you see small, white segments that look like sesame seeds or rice grains around your cat’s anus or on their bedding, your cat has tapeworms. These are almost always caused by ingesting a flea during grooming. While disgusting, they are the easiest parasite to treat.

Elanco Tapeworm Dewormer (Praziquantel)

The industry standard for killing tapeworms. Praziquantel dissolves the parasite within 24 hours. Note: This does not prevent reinfection; you must also treat for fleas.

Check Price on Amazon →Parasite prevention in a giant breed requires vigilance. It means looking for the symptoms you can see (scabs, rice grains) and testing for the ones you can’t (protozoa). By keeping your Maine Coon on a high-quality monthly preventative and reacting quickly to changes in stool quality, you protect their ability to absorb the massive calories they need to maintain their size.

References#

- Gookin, J.L. (2006). Tritrichomonas foetus infection in cats. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery.

- Companion Animal Parasite Council (CAPC). Feline Heartworm Guidelines.

- Blagburn, B.L. (2018). Efficacy of spot-on formulations in long-haired cat breeds. Veterinary Parasitology.